Shimla Lower Bazaar Community Asset Mapping Report

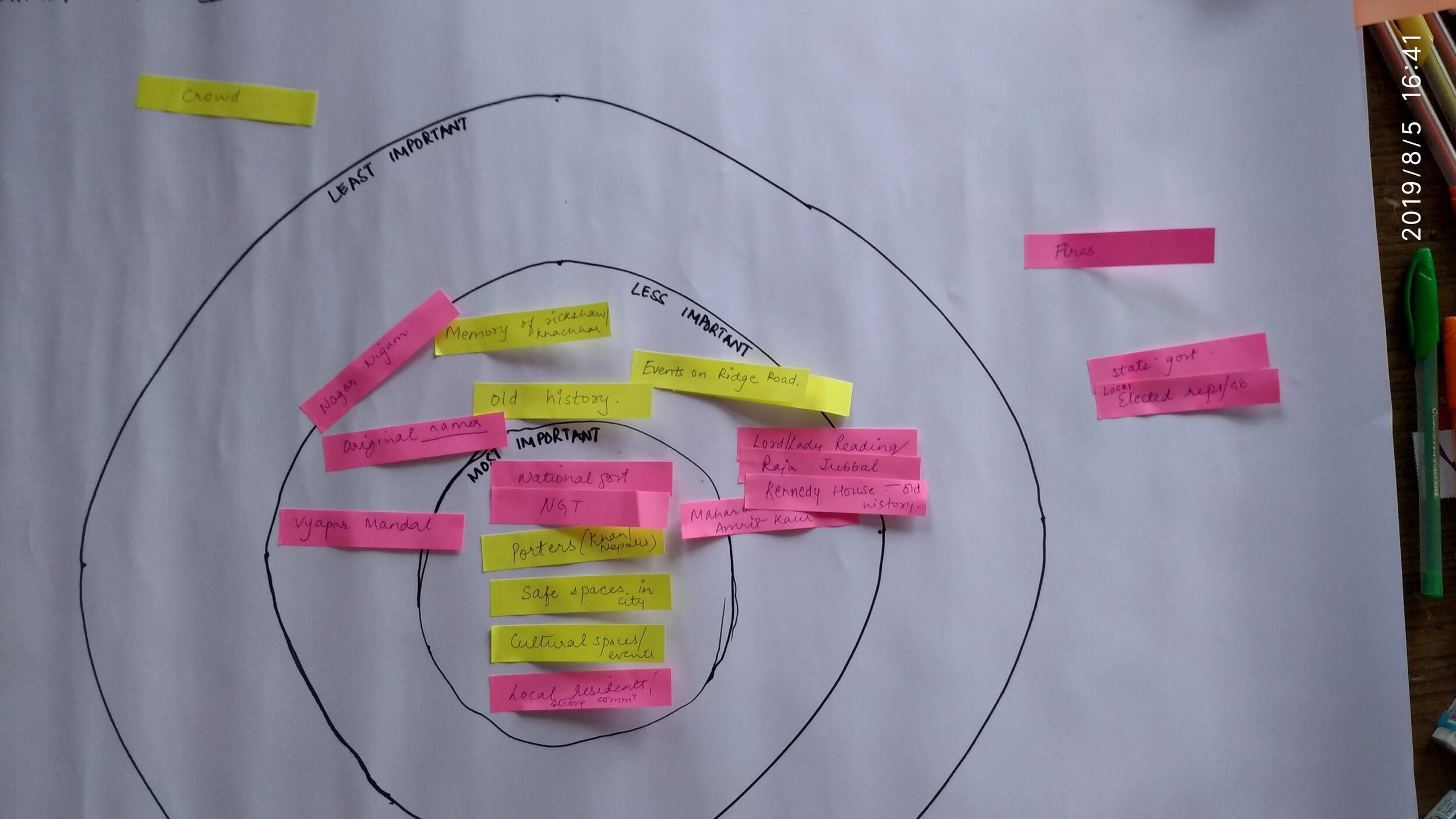

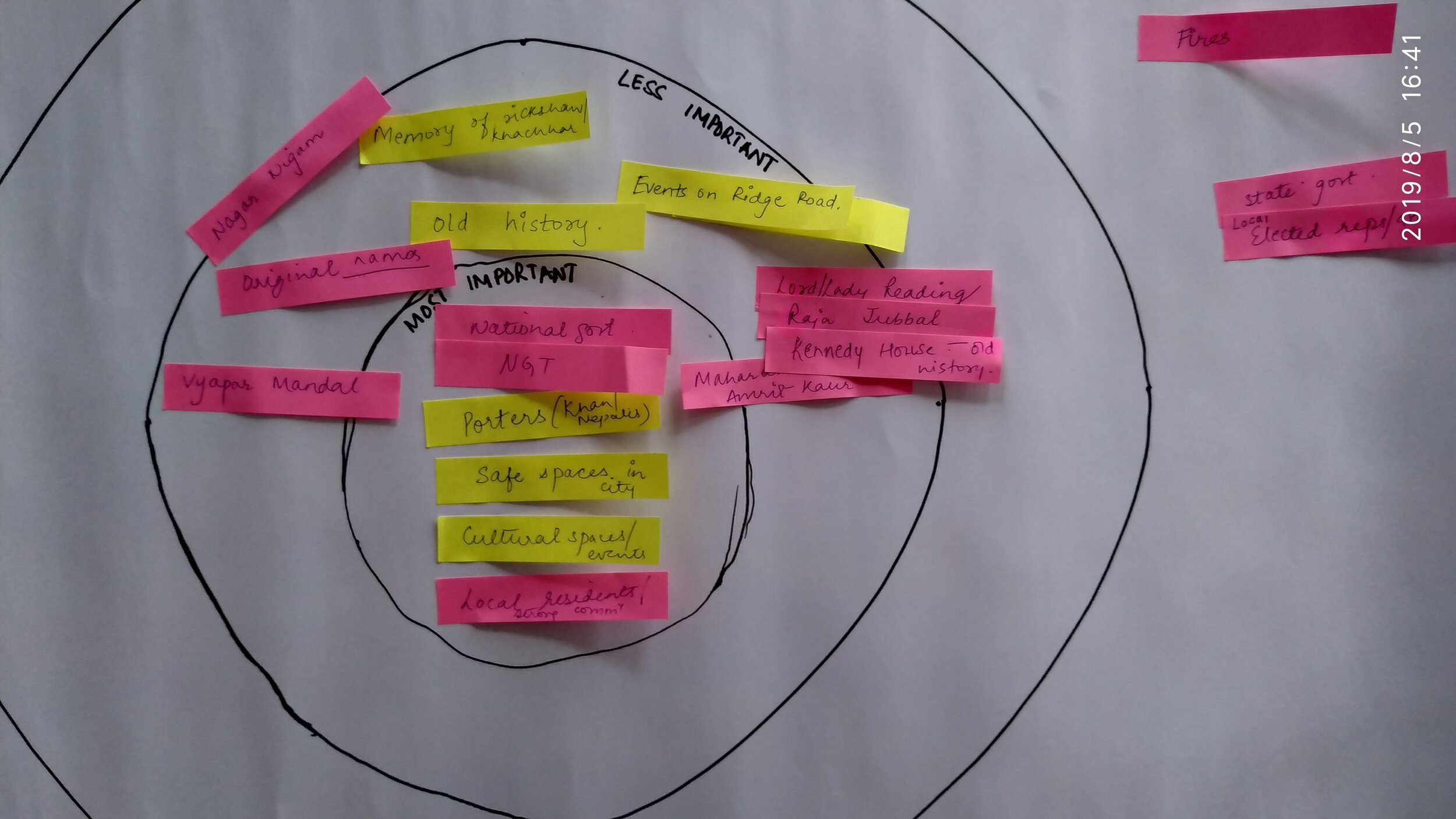

On August 5th 2019, the project team members conducted a Community Asset Mapping (CAM) workshop with business owners from the main commercial district of Shimla, known as Lower Bazaar. The method followed was similar to that described in previous blog entries. The discussion was anchored in the physical space of Lower Bazar but encompassed a wide range of issues relevant to the entire city.

The Lower Bazaar area – a serpentine stretch of about 1.5 km lined by shops and open-air stalls – has been the subject of numerous redevelopment plans. Under the smart cities scheme too, it is proposed to be demolished and reconstructed, with the aim to streamline the structures and open up the valley-side view for tourists. The realization of such proposals as consistently been blocked by logistical difficulties and environmental clearance issues. In its latest ‘smart city’ incarnation, the redevelopment plan for Lower Bazaar is more ambitious than ever before, and therefore met with more cynicism.

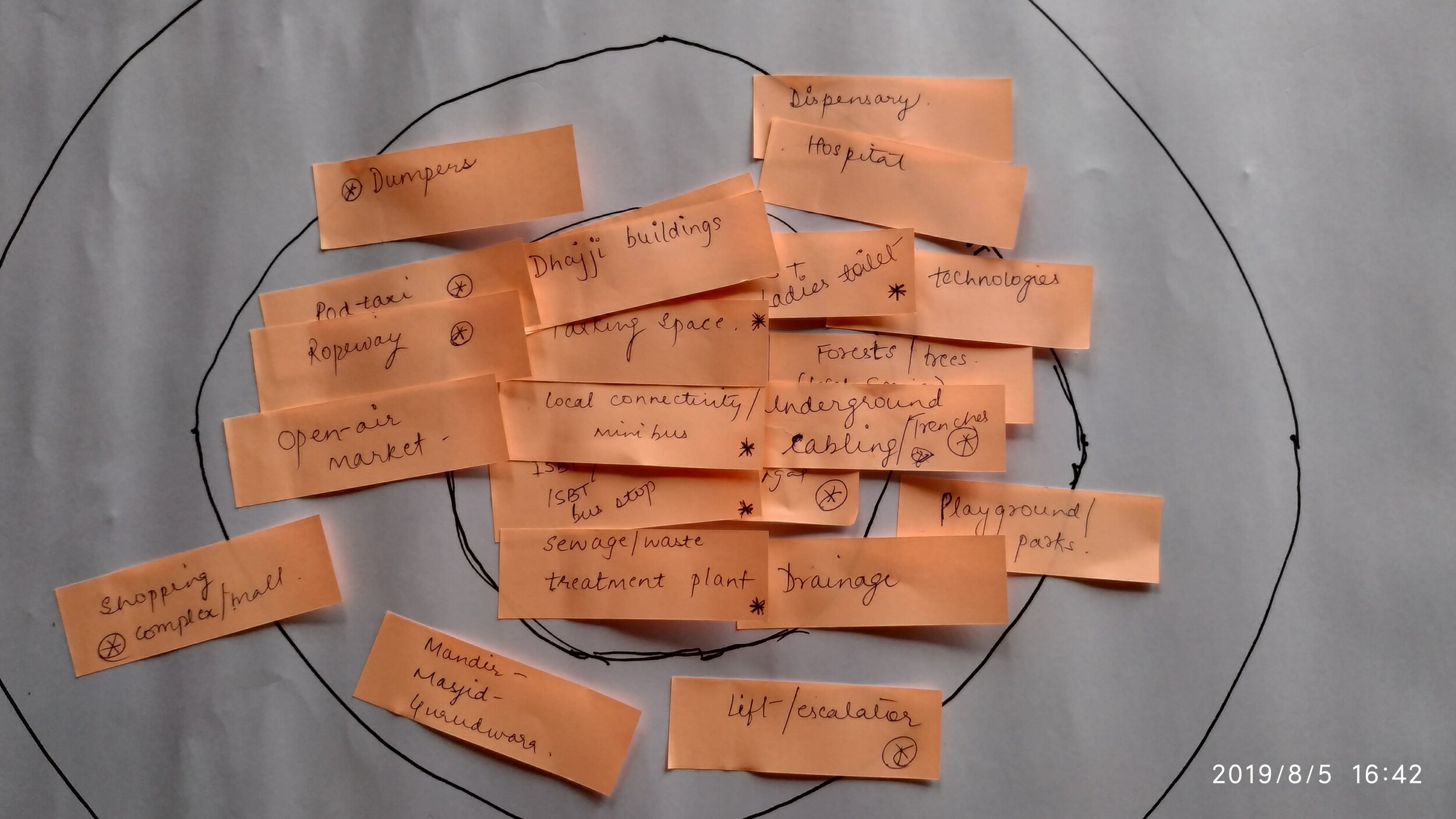

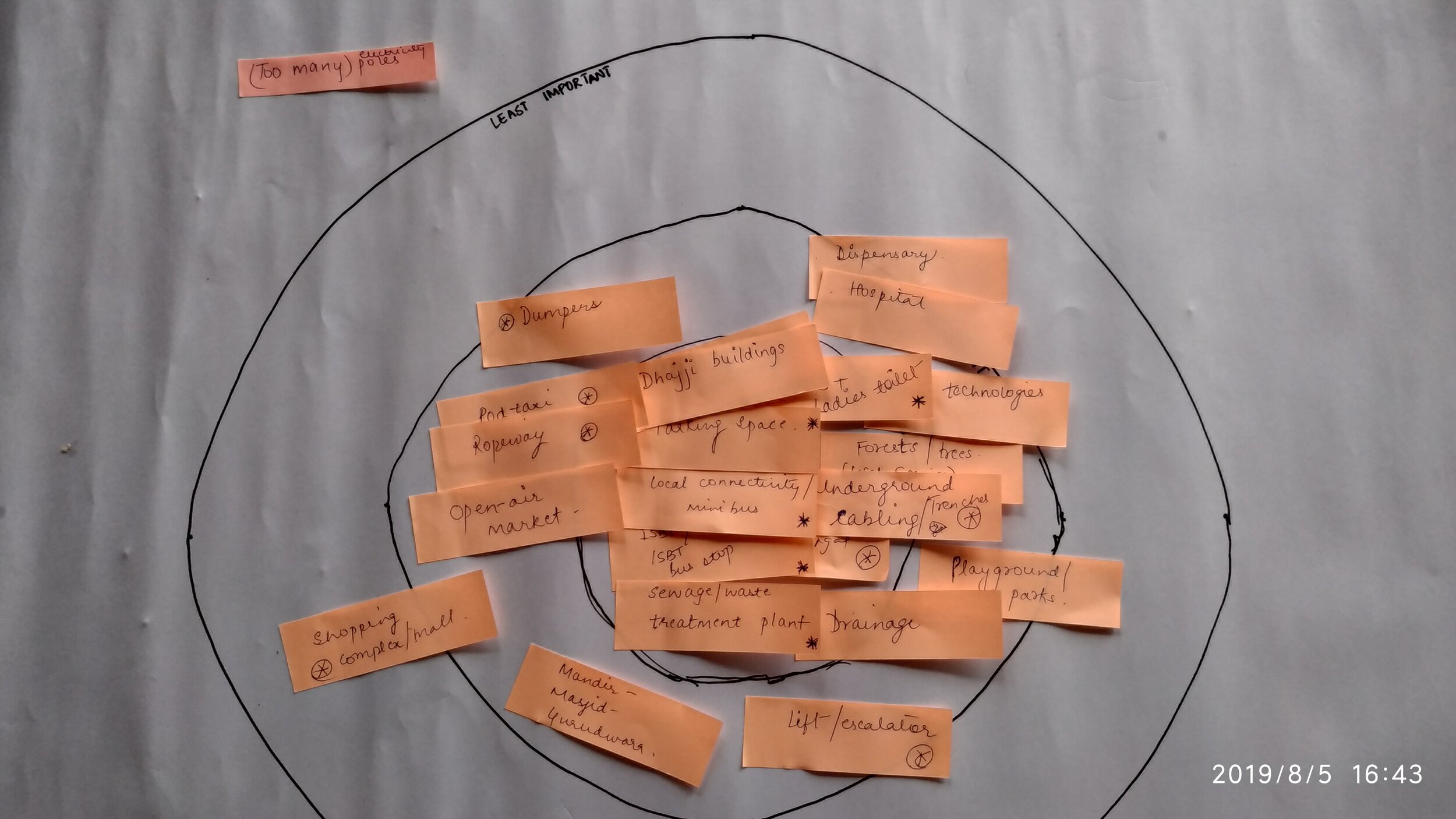

The first round of discussions focused on the asset category of infrastructure, followed by a second round focused on people and events. The assets identified within this category were largely valued due to their age and historic significance. For instance, the old dispensary was identified as an iconic feature of the bazaar around which later developments took place. The religious structures such as the temples and mosques were identified as sacrosanct – to be strictly protected from demolitions and redevelopments. The integral relationship between socio-cultural value systems and the built-environment was made evident through these discussions.

The discussion around the logistical difficulties of redeveloping a mammoth commercial complex like Lower Bazaar inevitably turned to a discussion of the intrinsic difficulties of navigating a hilly terrain. The participants reminisced about the use of ‘dhajji’ – a mixture of different kinds of crushed stone and clay – as a building material that was resistant to landslides and earthquakes. It was later discarded in favour of brick and mortar as the construction technology evolved. While this allowed people to build beyond two storeys, it also compromised on the durability of the buildings in a mountain setting.

Another aspect of urban planning that was highlighted by the participants was that of drainage. The close connection between a robust drainage system and the ability to prevent landslides was discussed. Besides political will, this requires a generous investment. The participants identified the central and state level governments as key actors in this, while commenting on the limited powers vested in the hand of the city-level administrators.

The participants also ruminated on the rising population of the city. At the time of its establishment as the summer capital under the colonial regime, the city was planned to host not more than 25,000 inhabitants. The current population stands at close to a hundred and seventy thousand and steadily growing. At the same time the city witnesses a high seasonal footfall of tourists. The tourism industry was identified as a key asset that needed to be nurtured and placed at the core of all planning efforts.

With regard to Lower Bazaar itself – the look and feel of the place, the ‘charm’ of the bazaar was recognized as a prized asset. This meant that any redevelopment plan would need to preserve this charm by emulating the experience of a stroll through the bazaar. The Old Inter-State Bus Terminal grounds were identified as one of the possible locations where such a project could succeed.

By Srilata Sircar, Project Research Associate